ALESIA 52 BC - BOURGOGNE

Despite being dubbed barbaric, pre-Roman Gaul was a land of considerable wealth. Western Europe was rich in gold mines, and the locals were fond of displaying this wealth in body jewelry. They were minting gold coins from the fourth century BC onwards. By comparison, at the time of Caesar’s invasion of Gaul, Romans continued to use only silver and bronze coin. Pre-Roman Gauls were also experts in blacksmithing and forged high-quality ore and goods, including plowshares, farm tools and, of course, swords. They had a calendar more advanced than that used by Rome and, while they did not leave any written record, they maintained a class of professional intellectuals—known as Druids—who were guardians of an oral tradition of literature and history, as well as medical, scientific and religious knowledge. They were also the guardians of a large body of sophisticated laws.

Gallic society was structured around the clan and the duty of clan members. Clans tended to be centred in towns, which were trading centres often closely connected to mining operations. A Gallic farmhouse was usually a large, rectangular, two-story building, the interior of which sometimes consisted of a single large common room and sometimes many smaller chambers. Gallic towns were often connected to each other by wooden roads, many of which were eventually paved over in the Roman style.

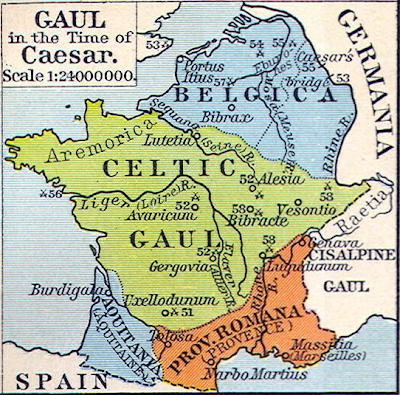

Map from the heritage-history.com website

heritage-history

Militarily, it was often difficult to tell the difference between a Gallic and Roman soldier. Both employed large shields, and both wore formed helmets. In many ways, Gallic armaments were superior to those of the Romans. In fact, following the Gallic Wars, Roman helmet design became more similar to those of the Gauls, incorporating characteristic Gallic cheek guards. Gallic shields were man-sized and highly decorated. Again, Romans subsequently adopted the Gallic style shield as their standard issue. Gauls were also proficient in the use of light spears and javelins. Although they made little use of archers, they did make effective use of cavalry. As they tended to apply military tactics of movement, they lacked siege machines.

As victors tend to write history, it was expedient for Rome to play up the “barbaric” aspects of Gallic society. In battle, this was notable in the seeming lack of tactical discipline of the Gallic horde. Similarly, because the Gauls had a habit of collecting the heads of defeated enemies, the Romans pointed to this as an indicator of savagery.

If we appreciate the wealth of Gaul, Julius Caesar’s interest in these “wildlands” makes more sense. Julius Caesar was an ambitious senator in his 40s, but by 61 BC was deeply in debt. He needed cash to ward off his creditors and a military adventure to boost his career. In Gaul he saw an opportunity to meet both these demands.

In 58 BCE, Rome was presented with the pretense it needed to invade Gaul. The leader of the Gallic Aedui clan, Diviciacus, had been deposed in a coup and fled to Rome to seek assistance in reclaiming his position. Diviciacus was seemingly well-mannered and made the rounds of the best houses in Rome, but was unable to garner support for a military adventure until he latched onto Julius Caesar. Seeing the opportunity, Caesar led a campaign to convince Roman’s leadership that the Gauls posed a serious threat to Rome itself. In particular, he singled out the Helvetii as a serious threat. The basis for this was that the Helvetii were engaged in a mass migration into modern-day France, which was caused by a combination of population growth and pressure from Germanic and other peoples expanding into their territory from the east. Caesar persuaded the Senate to appoint him “Protector” of the Gauls. This turned out to be an ironic title, as over the next several years it is estimated that Roman forces slaughtered upwards of one million Gauls and enslaved one million more.

The legions’ invasion of Gaul was not easy. While Rome had the advantage of a disciplined professional army, the Gauls had the advantage in numbers and an ability to unite, at least for short periods of time, in a common cause. The Romans were also beyond their supply lines and so often short of food and forage.

The Dying Gaul (Il Galata morente), Roman copy after a sculpture situated in the Pergamon Acropolis

The Roman conquest of Gaul began in earnest in 58 BCE. Major engagements occurred throughout modern France, with a general theme of Roman success (in chronological order,: the Battles of Arar, Bibracte, Vesontio, Aisne, Sambre, Atuatuci, and Morbihan Gulf). Throughout 55-53 BC, the legions continued to assert Roman dominance over Gaul, stamping down any resistance by the Gauls and warding off Germanic incursions. By 53 BCE, Caesar had ten full Legions in Gaul—a force of 40-50,000 men.

Satisfied with his campaigning so far, Caesar returned to Italy in the summer of 53 BCE, after leaving garrisons scattered throughout occupied Gaul. But he was soon recalled to Gaul due to a new “emergency”: the “Great Gallic Revolt.” A charismatic new leader had emerged. While his real name is unknown, the warrior known as Vercingetorix, a title meaning “over warriorr”, emerged as the leader of a coalition of tribes, of which the Helvetii were the most predominant. During a convenient uprising in the town of Cenabum (Orléans), Vercingetorix’s forces attacked and destroyed the local Roman winter garrisons. Caesar responded by force-marching his army through deep snow in winter weather and falling upon the Gallic forces.

Most of the major battles between Romans and Gauls for the rest of the Gallic Wars were a series of sieges at Gorgobina (possibly Saint-Parize-le-Châtel or La Guerche [Niève]), Vellaunodunum (possibly at Montargis or Château-Landon), Cenabum (Orléans), Noviiodunum (probably Neung sur Beuvron), Avaricum and Gerovia.

While the Gauls suffered defeats, throughout 52 BCE Vercingetorix was able to maintain his authority and implement a scorched-earth policy: the Gauls would burn towns and villages to deny the Roman army food and other supplies, and would also stage harassing raids and attacks on Roman foraging parties. The Gauls destroyed at least twenty towns that lay in the Roman army’s path. The one town the Gauls decided not to burn was Avaricum (near present-day Bourges), which the inhabitants tried to defend against the Roman forces. This was a mistake: the Romans slaughtered them all. The massacre at Avaricum persuaded the Gauls that Vercingetorix’s strategy of avoiding direct conflict with the Romans and denying them the supplies they needed was a good idea.

The one Gallic “victory” in this campaign was at the Battle of Gerovia in May 52 BCE. The site of this battle is at La Roche-Blanche near Clermont-Ferrand. Gerovia was in a strong defensive position at the top of a steep hill. Direct assault was not possible, so Caesar began a siege. He split his forces, stationing one camp on a small hill while the rest of his forces remained on the plains. The two camps were joined by a three-metre-wide trench. Caesar couldn’t maintain this entrenchment as ten thousand infantry of the Aedui clan (a former Roman ally) advanced to attack his position. While this threat was headed off, a possible revolt by the Aedui inspired Caesar to abandon the siege and move north to join all of his Legion together. Caesar, as you may know, was not one to admit defeat, and he organized an attack on Gerovia. He got his chance on a day when most of the Gallic defenders were away from the main camp building defensive fortifications on a different part of the hill. This face-saving attack went well for the legions, but—contrary to orders—several legions went past the captured camp and attempted an assault on the town walls. This ended badly for the Legions and forced a chaotic withdrawal. The next day, Caesar drew up the legions for battle, but Vercingetorix refused to take the bait. With that, the legions departed and Gerovia was saved.

Vercingetorix’s next move was to march his army, which included about fifteen thousand men on horseback, to the fortified town of Alesia (situated on Mont Auxois above the modern village of Alise-Sainte-Reine). Caesar followed on the heels of Vercingetorix with six legions and a large number of German cavalry. The settlement of Alesia occupied high ground and Caesar decided to starve out the defenders rather than engage in open battle. To accomplish this, the Roman turned to their other field of expertise: military engineering.

The legions dug two trenches, one 6 metres deep and another 4 metres deep, which they filled with water diverted from a nearby stream. They also built a rampart approximately sixteen kilometres long, topped by a stockade wall with watchtowers and gates. This wall was also defended by spikes to prevent opponents from scaling it, and dead drops and other traps were placed in the ditches. However, before the siege fortifications were complete, Vercingetorix sent out riders to his allies to gather a relief force. While Vercingetorix did not seem to know it, a force reportedly as large as 320,000 warriors was assembled and began the march to Alesia. Caesar learned that this army was headed his way and came to an ingenious solution: he had the legions build a second circuit wall around the first one, consisting of 20 kilometres of ditches walls, ramparts and traps. By this method, the legions were protected from attacks from Alesia and from the relief force.

As the siege of Alesia progressed, the defending force began to run out of food. The warriors in the town decided to send out all non-combatants, including the elderly, women and children. They were forced into the area between Alesia and the Roman line. Caesar denied their pleas to pass through the lines and did not give them food. Most of them probably died from starvation.

The relief force arrived and began to attack the Romans’ outer defensive positions. At the same time, Vercingetorix led raids out of Alesia to attack the Roman inner positions. The outnumbered Romans in their well-made fortifications withstood these assaults from both sides. After five days of fighting, Vercingetorix realized the Romans could not be defeated, and as the defenders of Alesia were out of food, he decided, in consultation with his warriors, to surrender. The Roman writer Plutarch claims that Vercingetorix put on his most colourful armour, had his horse groomed, and rode out of the city to face Caesar. He reportedly rode a circle around the Roman general before dismounting, removing his armour and surrendering himself.

Vercingetorix was taken to Rome and imprisoned for five years. He was eventually put on display during a twenty-day celebration of Caesar’s victories and then garroted to death. During the same period, Caesar further augmented his power and eventually became dictator of Rome.

After Alesia, the Gauls were unable to mount any further significant defence. Throughout 51 BC the legions consolidated control over the province, including siege engagements at Limonum (Poitiers) and Uxellodunum (near Vayrac above the river Dordogne). After defeating the defenders of Uxellodunum, Caesar decided to set an example – rather than enslaving or killing them, he had their hands cut off and set them free.

ALESIA TODAY

Le MuseoParc Alesia

It is relatively easy to combine a visit to the Verdun Battlefields with a trip to Alesia, a 3.5-hour drive away. The drive takes you past the sites of the Battle of Valmy (1792), Champs Catalauniques (451) and the Battle of Laubressel (3 March 1814) via the A4 and A26.

Le MuseoParc Alesia Map - This is what you’re here for. The museum is excellent, with well-thought-out exhibits that include an outdoor reconstruction of the fortifications. The film is pretty cheesy but short. There are vents for children during the summer but fewer crowds the rest of the year. Allow two-three hours to visit. The restaurant is pretty good. Include with your ticket a visit to the hilltop ruins three kilometres away. Map And don’t forget the obligatory photo of the statue of Vercingetorix Map. Website: alesia Rank 10.

AROUND ALESIA:

Parc de L’Auxois: Map Aquapark and zoo. Bring your own food. parc-auxois

Château de Busy-Rabutin: Map is a stunning château with attractive grounds. chateau-bussy Rank 7

Château de Chateauneuf is a large hilltop castle on the outskirts of the beautiful artists’ village. Budget 1-1.5 hours to visit the Château. Map In the summer, there are all sorts of medieval-themed activities like roaming minstrels and baking demonstrations. chateauneuf.bourgogne Rank 9

L’abbaye de Fontenay" is a bit out of the way, but a must-see for those interested in Church history. In addition to the twelfth-century buildings, there is a beautiful garden. Map It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Allow one-two hours for your visit. abbayedefontenay Rank7

Fans of candy (and who isn’t?) may be interested in visiting the charming village of Flavigny, home to the anise-flavoured “les Anis de Flavigny.” Map The town is said to have been founded by one of Caesar’s veteran soldiers, Flavinius, around 52 BC. The town’s Benedictine abbey was founded around 500 CE, pillaged by English besiegers in 1359, and is today a candy factory. anis-flavigny In keeping with the candy theme, the exterior scenes of the 2000 movie Chocolat were filmed in Flavigny. Rank 7

Consider a side trip to the Canal de Bourgogne.Map You can bicycle along a portion of it or settle in for a day- or week-long cruise. The Canal connects the river Yonne at Migennes with the Saône at Saint-Jean-de-Losne. Canal_de_Bourgogne

Nearby Dijon has a pedestrian-friendly center, medieval and renaissance architecture, and plenty of good restaurants. These features make Dijon a good place to anchor any visit to Bourgogne.burgundy-tourism The city also has a tourist trail that includes twenty-two stops throughout the city’s historic neighbourhoods (the parcours de chouette). A bronze owl identifies each stop. Maps are available at all Dijon tourist offices. destinationdijon Rank 7

Dijon also hosts a pretty good Museum of Fine Arts Map , featuring a hodge-podge collection. dijonfine-arts-museum

Dijon was also the site of three Battles of Dijon fought between Prussia and the “Army of the Vosges” in 1870 and 1871. The Army of the Vosges was a motley crew of five thousand to fifteen thousand volunteers from Italy, France, England, Ireland, and America, all led by the famous Italian general Guiseppe Garabaldi. battle-of-dijon